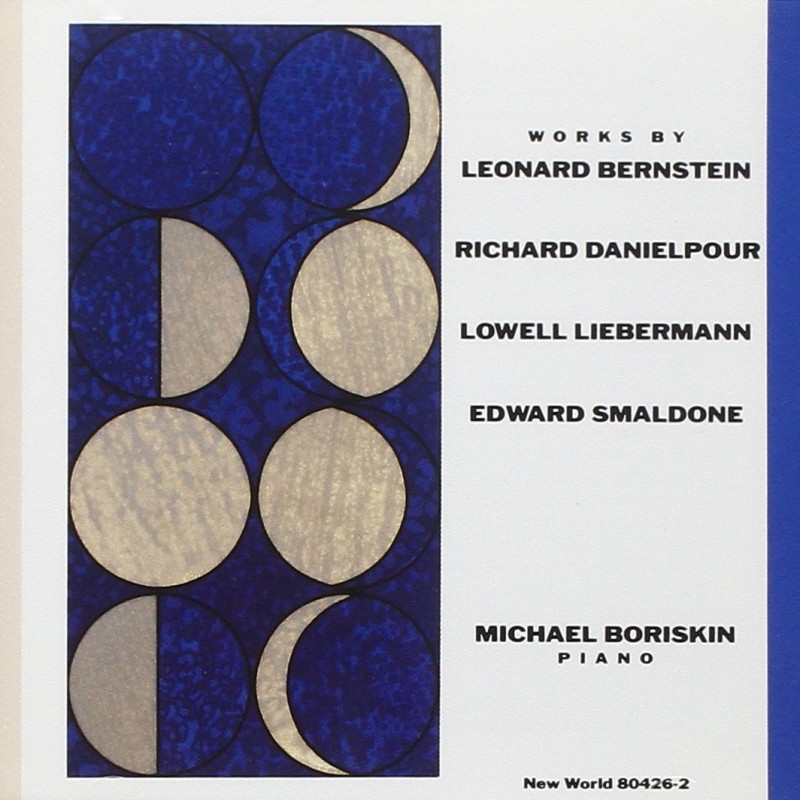

Apart from musical considerations, it is entirely appropriate that the work of Leonard Bernstein (1918-1990) stands beside the compositions of three younger Americans on this program of recorded premieres. By example and deed, Bernstein served like no other major American artist as a true role model for at least a couple of generations of aspiring musicians in this country. Moreover, his eclecticism as a composer and performer exemplified the polyglot nature of the arts in America.

Among the composers to whom Bernstein, in his last years, gave encouragement was Richard Danielpour (born in 1956). Danielpour’s music is expressively urgent and unconstrained, and instrumentally flamboyant; harmonically wide-ranging, it rarely strays long from a tonal anchor. Much of his work is concerned with psychological journeys, which are often made explicit through titles, texts, or other clear associations. In his Piano Sonata (1986), such extramusical allusions are only implied by the striking contrasts and highly charged atmosphere. The duality embodied in the piece recurs frequently in his music: light and dark (in both the coloristic and metaphysical senses), outer and inner emotions, and public and private lives are represented by music that is exuberant and ruminative. The one-movement Sonata is subdivided into five clearly defined connected sections, alternating slow and fast; arranged as an arch, the first and last parts correspond to each other, as do the second and fourth. The piece opens by vigorously proclaiming a motto-like motive (G sharp—A sharp—B—G) that will generate much of the ensuing music. The final section, which follows a rapturous climax, amplifies the opening material and then gradually subsides in a long peroration. The contrasting second and fourth sections are ecstatic and mercurial, while the rich chorale in the central section is an oasis of calm at the work’s core.

Over the course of a protean career, Bernstein composed twenty-nine musical vignettes, which were published in four collections called Anniversaries. Three sets, containing sixteen works in all, were issued between 1943 and 1954; the remaining thirteen pieces, written at various times from 1964 to 1988, appeared in 1989. Like their predecessors, the compositions in Thirteen Anniversaries are simply designed, modestly scaled, and generally intimate. Some of the pieces display considerable richness and expressive power, despite their reserve, while others are witty and gently playful. Bernstein’s art, often as extravagant and colorful as its creator, is distilled here to a purity that is at once disarming, genuine, and affecting. These lucid, evocative little works arose out of diverse circumstances; they were usually conceived in the abstract, and not especially intended as portraits of their respective subjects (family, friends, or musical associates).

The music of Edward Smaldone (born in 1956) deftly combines a jazz-inflected vocabulary with certain Schoenbergian principles (especially from the pre-serial, “free atonal” period). In the etudes Smaldone composed for me in 1990, four colorful, semi-abstract paintings by a New York artist, Irving Abram, are transformed into a musical idiom. Out of Eden is primarily a study in repeated notes upon which are juxtaposed widely leaping chords; like the painting to which it refers, it attempts to capture the

drama of the moment of expulsion, and also reflects, in the music’s lyrical passages, upon the joys of life lost as a result of that banishment. Sonata, which is vaguely suggestive of a chamber music duo, is concerned with fleet passage work and abrupt registral changes. In the dark-hued Secret of the Earth, four layers of varied sonorities, rhythms, and dynamics mirror the painting’s representation of this planet’s many tiers between surface and core. Django’s Lick, recalling the animated, freewheeling style of jazz guitarist Django Reinhardt (1910- 1953), consists of two studies in one: a driving, ostinato- like drill of left-hand leaps and an arduous workout in right-hand double-notes and widely spaced runs. The four pieces are framed by the coruscating Introduction and an identical, but muted, Epilogue, which reinterpret Chopin’s pioneering C Major Etude, Opus 10 Number 1.

An avid student of art and architecture, Lowell Liebermann (born in 1961) has long been intrigued by the strange, ornate carvings called gargoyles, which embellish many old churches and palaces; often exceedingly bizarre in appearance, they were thought to help repel evil spirits. Demons seem to hover around Liebermann’s own Gargoyles (1989), a set of four highly contrasted etudes, which maintains an eerieness and sense of mystery even in its more placid moments. The title is meant simply to characterize sharply drawn sketches of a florid and macabre nature, rather than to suggest any actual musical depiction of these ornamental grotesqueries. Liebermann unabashedly looks back to the Romantic era, simultaneously remodeling the idiom and reveling in its conventions. The first piece is a feverish study in double notes, wide leaps, and quickly changing dynamics and articulation. The second features legato octaves above an ostinato bass. The third is a study in legato melody accompanied by a gently undulating figuration distributed between the hands. The wild tarantella deliriously concluding the set is a diabolical endurance test.

—MICHAEL BORISKIN