Astral Artists showcases Aaron Jay Kernis

Renaissance traps, successfully avoided

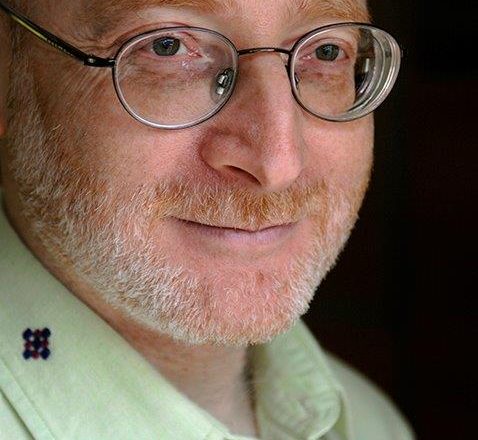

Tom Purdom

March 22, 2011

Aaron Jay Kernis finished his two-year stint as Astral Artists’ first composer in residence with two spectacular pieces that starred a spectacular soprano. Kernis has been blessed with a genius for choosing texts. For his first entry on Sunday’s program— his 1991 Simple Songs— Kernis picked texts by the medieval mystic Hildegard von Binge and the Sufi mystic Rumi, and combined them with three of Stephen Mitchell’s very free (but very reasonable) translations of the Psalms and other works.

Kernis’s vocal lines are just as simple as his title indicates, but they always embellish the text, and Kernis never indulges in unnecessary musical flourishes. The piano accompaniments in Simple Songs are more complex, but they’re just as appropriate and unaffected.

Disella Larusdottir opened Simple Songs with an attention-getting proclamation of Hildegarde’s ode to the Holy Spirit. Larusdottir possesses a bright, penetrating voice that seems devoid of weak points, and her dramatic entrance immediately told everyone in the audience that we were hearing someone special announce something special.

Operatic singers, beware

Many operatically trained singers flub when they turn to art songs because they sing everything like it’s a big aria. Kernis wrote Simple Songs for that kind of big-voiced approach, but Larusdottir proved she can make a song float, too, when she turned to his setting of Psalm One’s serene picture of the contented man and woman. Her contributions to both Kernis pieces combined vocal power with the nuanced expressiveness art songs require.

The main event of the day was the premiere of Kernis’s setting of excerpts from Renaissance dance manuals, commissioned by Astral Artists (with funding from the Pew Foundation) and composed for soprano, flute, viola, harp, and percussion.

Kernis avoided the two traps that modern composers can fall into when they venture into the domain normally occupied by early music groups like Piffaro. He didn’t try to imitate Renaissance music, nor did he produce a sentimentalized version of Renaissance balls and festivals.

Telling a Renaissance story

The result was a musical invocation of an older society’s dreams— a 21st Century version of the vision that Renaissance dance masters tried to create when they produced their fêtes and pageants.

The Kernis vision opens with a long description, in Italian, of a Renaissance dance festival, with the soprano singing over a happy jumble from the instruments. It also includes excerpts from dancing instructions and a final hymn to youth and pleasure.

Larusdottir has developed an effective story-telling style, which she put to good use throughout the lengthy first section. Kernis’s five long movements create a musical marathon in which the soprano sings almost non-stop, and Larusdottir maintained style and power all the way to the end.