Seeking To Revive Classical Music

LOOK at the fine print: Michael Boriskin’s name can be found on programs at the 92d Street Y in Manhattan, where he serves as a moderator, an artistic consultant and a performer; in listings for National Public Radio, where he has a series on 20th-century music, and in the tables of contents of various books and magazines.

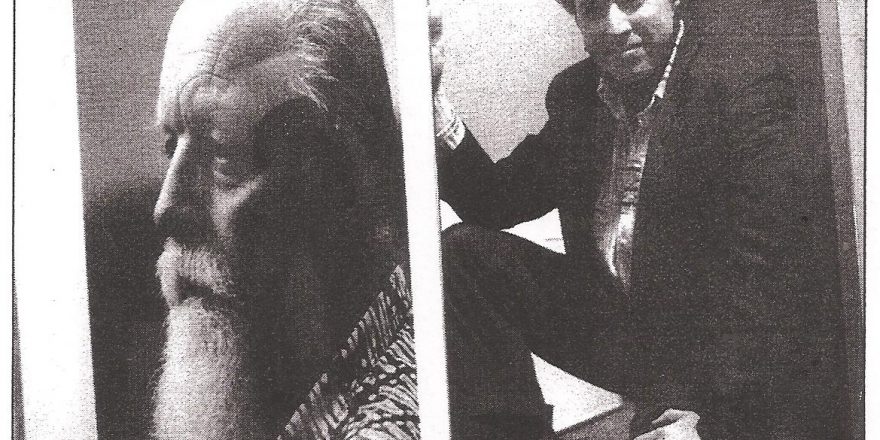

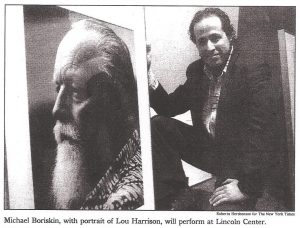

But Mr. Boriskin, a musical Zelig, is primarily a pianist, and it is in that connection that he will make his debut at Lincoln Center tomorrow night at 7:30. In a program at the Walter Reade Theater, Mr. Boriskin will perform the piano works of Lou Harrison, the American composer who marks his 80th birthday this year. Lincoln Center is honoring the occasion with a cluster of concerts and events, and Mr. Boriskin is lending his varied talents to them.

One recent morning, Mr. Boriskin left his Westchester home early to supervise the installation of Harrison memorabilia in the Furman Gallery, which is adjacent to the Walter Reade Theater behind Alice Tully Hall. Mr. Boriskin curated the exhibition, combing through material at the Performing Arts Library at Lincoln Center as well as obtaining musical scores, photographs, Harrison artwork and correspondence from the California-based composer’s archives.

Just the day before, Mr. Boriskin had performed at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, and the next day he was scheduled to give master classes and recitals at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles. Yet despite the madcap schedule, the installation proceeded with calm efficiency as well ordered as Mr. Boriskin himself.

He has a broad, warm smile and a precise, direct manner that works to his advantage on the concert stage. Music critics speak of a dazzling virtuosity enhanced by a natural gift for communication.

Even the Lincoln Center debut is tied to a larger purpose: that of helping others discover the same delight Mr. Boriskin said he finds in Harrison’s music. While the event is undoubtedly good for his career, he barely mentioned those prospects during an interview, dwelling instead on the importance of revitalizing the classical music scene. ”Unless there are some courageous visionary ideas” brought to the field, he said, ”we will be playing ourselves into oblivion.”

Mr. Boriskin is among those trying to breathe life into a form known for worship of the dead. Not that he does not revere Beethoven and others; he just does not think the recycling of the old and the virtual exclusion of the new is good for any art form.

”It’s unthinkable for a theater company to do only Shakespeare or for an art museum just to show old works,” he said during a break in the installation. ”Yet we really devalue the efforts of living musical creators.”

By ”we,” he said, he means programmers and listeners whose uneasy pact allows little of the new to poke through the popular selections. Mr. Boriskin does not blame audiences for wanting to spend their money on music they know and love; composers themselves, who dealt in esoterica for much of the past century, ”have to take a certain responsibility,” he said.

Other factors have also led to what he calls the marginalization of classical music. These, he continued, include the rise of the recording industry and the decline of the family amateur hour, when young and old grabbed their instruments and played together. The coup de grace was the loss of music education in many public schools nationwide and the further shrinking of the knowledgeable audience, he said.

”This all leaves us at the end of the 20th century basically cut off from people like Lou Harrison, whose music has rarely figured on the programs of mainstream organizations,” Mr. Boriskin said. ”We have been left impoverished, going back again and again to the old material.”

Mr. Boriskin’s face brightened. ”Hayden, Beethoven and Schubert wrote music to get a rise out of people,” he said. ”But we sit around in such conformity. I’d love to bring the atmosphere of a really good jazz concert, where there’s a palpable sense of people enjoying themselves.

”This music is fabulous. It’s a gas. One lifetime is not enough for this extraordinary music. But we’ve hermetically sealed it off.”

Do not look for Mr. Boriskin in a tuxedo on stage, because he has begun to dress down. ”I like to be appropriately attired for a nice evening out in the late 20th century,” he said, ”as opposed to dressing up as though I’m going to a formal ball in a castle in 1855.”

Do not expect him to lull the listener with genteel melody, either, or to provide a backdrop for daydreams. He is there to captivate, disturb and enrage, he said, and he will give the audience a chance to ask questions later.

Coincidentally, the widespread decline in musical literacy has a silver lining, Mr. Boriskin observed. ”Young people don’t know what they’re not supposed to like,” he said. ”Treat them to some sophisticated and snazzy new work, and they think it’s really cool.” He frequently travels to colleges and has recently been named an affiliate artist and teacher at Purchase College.

As he spoke, his recent recording, ”The Equal-Tempered Lou Harrison,” soon to be re-released on Sony, began playing over the gallery’s audio system. The music, as Mr. Boriskin had promised, was lively and not the least formidable.